Chapters

Transcript

MATT SELMON: Good morning. I hope you can hear me. Welcome to The Vein Center, where we're broadcasting from this morning. And thank you for getting up and sharing your morning with us. We thought this was an opportune time to go over vein disease management, as we're celebrating our 10th anniversary of the Austin Heart Vein Center. We did our first cases in July of 2010. And so we're enjoying new space and an anniversary of sorts. And so we thought this would be a great time to go over vein disease management and update. We'll also talk a little bit about deep venous management as well.

So the things we'd like to touch on this morning are venous insufficiency, which is what we manage here in the Vein Center, along with DVT and May-Thurner. We'll talk about a little bit the diagnosis, indication, and rationale for treatment and a little bit about the procedures and the devices that we use, some of the new devices. Then we'll talk a little bit about guidelines in cases.

So just to get in and get started, venous insufficiency. Our bread and butter here at the Vein Center is managing venous insufficiency. We use thermal ablation for most of the patients, but we also do sclerotherapy and microphlebectomy, which is part of the management of superficial venous insufficiency.

So what is venous insufficiency? A lot of you know well what venous insufficiency is. There's a lot of misconceptions about it. This is what your patients see when they go to the website. This is actually pretty good. It comes from Web MD. There's a lot of information out there. But basically, venous insufficiency is a problem with the blood flow in the veins of the legs coming back to the heart. It's called chronic venous insufficiency or stasis, because there's very little flow in the skin. Veins have valves to keep the blood moving in one direction. When they don't work, it creates pooling in the legs, leads to varicose veins and other problems. So this is what your patients see, and they may be asking you questions about it.

We're proud to have made this poster, which is available to you if you'd like a copy of it, either digitally or a real copy. It shows the anatomy, both the superficial and the deep, along with a little bit about May-Thurner syndrome, which we're going to talk about some of the basic pathophysiology of the venous valves and how the venous hypertension, high pressure in the veins, creates problems with skin and varicose veins.

So venous disease is incredibly prevalent. Some estimates have it in half of the population in the United States. At the most conservative estimates, there's probably at least 25 million symptomatic people in the United States with venous disease. And only a fraction of those actually seek treatment for it. So that's a huge unmet clinical need that we face.

So why do we have such a high prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency? I think partly because we all get older at some time. Half of us are women. There's hormonally mediated damage to valves, especially during pregnancy. So we get older. The smooth muscles and the veins don't work as well. Collagen and especially the elastin in valves starts to deteriorate with age. A lot of people have clots in the veins that the inflammation pretty much destroys the valves.

So anybody with DVT gets a post thrombotic syndrome, which destroys the valves. As we get older, then the calf muscle pump, which we rely on the blood flow back up, becomes less active. And then there's more chronic proximal vein compression that we see contributing to kind of venous insufficiency. That's classically May-Thurner syndrome, and we'll talk about that in just a bit.

So heredity. These are two of my patients. This is a grandmother and a daughter who have literally the same vein. They both tell me that the mother in between them has the exact same vein on her knee, but I didn't have a chance to get a picture of that. But this is what we're dealing with with varicose veins from chronic venous insufficiency.

So heredity plays a huge portion of the causes of varicosities and chronic venous insufficiency. 70% of our patients will relay to us that their parents had venous insufficiency or their siblings. We see it more frequently in females than we do in males, especially women who have been pregnant. The [INAUDIBLE] proteanases that circulate during pregnancy along with the increased vascular volume pretty much destroy the valves.

And a lot of women describe venous insufficiency beginning during their pregnancies and never really totally recovering from it. And then everybody stands or sits, one of the two, during their occupation. And most people relay the onset of their symptoms to standing for long periods or sitting for prolonged periods during their job.

So what do we see with chronic venous insufficiency? It's clearly a spectrum, beginning with some swelling or discomfort in the legs. The lower in the legs you go, the higher the pressure and the more the symptoms. So it's usually down low in the legs that we get most symptoms. People describe in the calves especially cramping and a throbbing sensation, heaviness, or generalized discomfort. Ultimately itching, burning from stasis dermatitis, from poor venous circulation in the skin. And then ultimately as the skin becomes more and more involved, we get discoloration, red that then turns into brown and purple splotches and discoloration of lipodermatosclerosis and varicose veins and ultimately lesions that don't heal that turn into chronic ulceration, stasis ulcers.

So it is a progressive disease that usually happens over years with increasing pain, discomfort, and reduction in quality of life. Begins is the valves become competent, which creates high pressure in the legs or venous hypertension, which stretches the veins. And as the veins get stretched, the valves become even less competent and the symptoms become worse. It ends up creating varicose veins, swelling in the legs, ultimately changes in the skin from stasis dermatitis, and then ultimately venous ulcers.

I just want to make a distinction between the deep system and the superficial system. This is well described in this poster that we've made. The deep system is inside the muscle and fascia. The superficial system is outside the muscle and fascia. In the Vein Center, we deal with the superficial system. That's what we can treat. There's not as much that we can do with the deep system until there's clot, and then we can remove that. We're going to talk about that in a bit.

Also wanted to go over a little bit the role that ultrasound plays in managing venous disease. It's really become the gold standard. It's cheap, it's easy to do. As the years have gone by, the quality of imaging with ultrasound has gotten better and better. We use ultrasound from the very beginning to follow up in the process of managing venous disease from screening patients to diagnosing it to mapping the system.

We use it during the procedure, both during the endothermal ablation procedure, as well as sclerosing and phlebectomy become quite good at looking during phlebectomy to make sure that we've gotten all the large veins out. And we always do that at the end of the procedure. And then we do it in follow up afterwards to see how it's changed over time. So it's really an integral part of management of venous disease.

This is what it looks like. This is up at the saphenofemoral junction where the great saphenous vein connects into the common femoral vein. And you can see I think I have a little marker here. Maybe you can't see that. On the left panel, you can see a valve that's just flopping back and forth. And that's the problem that we have with reflux or venous insufficiency. You can see the red and the blue, the blood flow going back and forth through that valve. It should be a one way valve, but as the veins enlarge and the valves become incompetent, we see blood flow going backwards in the veins, which creates the venous hypertension.

By definition, anything over a half of second of reflex backwards is considered to be abnormal. So we can actually grade the amount of reflux. And that's helpful in terms of clinically following these patients. Grade one is anywhere below a half second to one second, and that goes up to grade four over four seconds. Actually, insurance companies require this to approve procedures, and it's helpful for the clinicians to get an idea of how much reflux there is in some of these patients to use it with clinical to assess how severe the disease is.

So what do we do about it? This goes way back not only decades and centuries but millennia. So there's actually very well documented treatment for this going back to more than 2,000 years ago. People have been trying to treat venous disease probably quite unsuccessfully is my guess for many, many years. And it's usually because of the pain and discomfort of the veins.

For many decades, especially in the 20th century, at least, the standard treatment was stripping. And we use the term stripping mostly to describe removal of the great saphenous vein. And this was done by surgeons in the operating room that involved ligating the saphenous vein up at the top right it goes into the saphenofemoral junction and then removing it from below, usually putting a tool or rod in and grabbing it and literally pulling it out. This was the treatment for decades and decades for severe venous insufficiency and had actually a pretty good rate of success. The problem was a high recurrence rate of symptoms. And that's almost certainly because of progressive worsening tributaries and accessory saphenous veins that were not treated with stripping, which over time get worse.

This is kind of what it looks like. This is an incision up at the top where it was ligated and then you literally pull it out. The problem with this is it really destroys a lot of the surrounding tissue. And there's a lot of morbidity in the sheath where it comes out and the surrounding veins.

So everybody back in the '90s started looking for a better way. And with new technology, both with radiofrequency and with laser and with the desire to take it out of the operating room and go into the office to treat it, people started looking for better ways to do it. And that's where initially VNUS, which is the first company to develop radiofrequency ablation, which is just heat, essentially, which actually got FDA clearance in 1999. Laser didn't get a clearance until 2002. But the technique really wasn't widely accepted until probably five to 10 years later.

This is what the radiofrequency first device looked like. You put the catheter in just below the knee and the femoral vein and the saphenous. Advance it up to the saphenofemoral junction. And then in segments of seven centimeters would ablate the vein going down the vessel.

Laser is pretty much the same technique except you have to put the laser in to the same spot and then slowly pull it back after turning it on. This requires numbing with lidocane before it's done. But there's always been a competition between laser and radiofrequency. We usually use radiofrequency. My personal preference is that I think it's a little more elegant, you see a little less bruising, less damage to the tissue around it, because it has to touch the vein wall to actually deliver the energy and the heat. And I think it's a little bit more elegant.

So if you look at surgical vein stripping versus intravenous ablation, this is done many years ago. But around 10 years ago, there was a tremendous amount of information and analyses of the literature and a meta analysis came to the conclusion that they're essentially the same in terms of success with a little bit of edge given toward percutaneous treatment. And certainly cheaper and easier than a surgical approach. And so pretty much everybody has now adopted endovenous technique for ablating the great and small saphenous veins and any tributaries or accessory saphenous veins that need to be done.

So who gets this? This is the definition of the indication that Medicare and the insurance companies used. They say that endovenous laser or radiofrequency therapy is indicated for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins associated with reflux of the great and small saphenous veins in the lower extremities. So most insurance companies require a certain size of the veins and a certain amount of reflux and a certain clinical presentation to approve the procedure. The contraindications obviously would be acute DVT, severe peripheral disease, which should be treated first, and then we proceed with the venous treatment. Obviously pregnancy is a contraindication for most things.

This is what the procedure looks like. We usually go in just below the knee. We put the laser, the radiofrequency device, up the near the saphenofemoral junction, slowly pull it back, and it simply heats the vein, it damages the endothelium, clots off the vein, and ablates it so that there's no flow. And the goal is to reduce the venous hypertension, allow the smaller, healthier veins to improve circulation through the skin.

After the procedure, we have the patients wear graduated compression stockings, thigh high stockings, for 48 hours without taking it off. We would like for them to wear it for two weeks just during the day. There is always a little bit of bruising and some tight feeling for a day or two afterwards. Usually doesn't require anything more than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or Tylenol. And we don't need an IV for this, and it's rare to use IV sedatives. But there is that option for some patients.

So what are the complications? The only real complication that we worry about is DVT. Fortunately, that's very rare. And pulmonary emboli are extremely rare. What we do see more frequently is superficial thrombophlebitis. And that can be up to 5% of the cases. That usually presents as a small area of tenderness. And it's usually from some tributary that has clotted off and become a bit inflamed. And that typically will go away within days to weeks. We do see occasionally some hyperpigmentation, and especially in young women we do worry about that. But it's unusual.

The other thing that we do see is what's called endothermal heat induced thrombus or EHIT. It's graded from one to four. That's when at the end of the ablation, up close to the saphenofemoral junction, we will sometimes see clot propagate back toward the deep system of the common femoral. If it reaches the deep system but does not encroach it, we call that EHIT 1. That virtually always recedes and goes away without any treatment. EHIT 2 is if it's less than 50% encroaching in the common femoral.

And we don't treat that either. That virtually always goes away. Repeat the duplex ultrasound in a couple of weeks to make sure. EHIT 3 is when it's more than 50% but non-inclusive, and we will treat that for between one to two weeks with coagulation and repeat the ultrasound. And EHIT 4 is DVT that we've induced, and that's rare.

So what are the results? This is all studies from almost 20 years ago at the very beginning, and this has held up, and these are some of the original studies that were done looking at the results. And this is what we quote now, because it's held up. What we see is about 95% to 97% occlusion at two years of the veins that we treat. We do occasionally see some of these veins re-catalyze. The veins generally want to be open and not closed, and some of them that are very large that we get an inadequate ablation will reopen, but it's less than 5% of the time. Typically we'll just go back and redo those.

So some patients require more than endovenous ablation. That's what we call axial treatment of the venous disease. And we always do that first and foremost, and we get the biggest bang for the buck with ablation of the saphenous vein. But it doesn't completely treat the patient. So we do have adjunctive care. Most of these patients get compression stockings and try to tell them we're not going to necessarily get them out of compression stockings at least when they travel or they're going to be sitting or standing for long times. But we do ambulatory or stab phlebectomy, where we will take out the varicose veins, and we do sclerotherapy, which is injecting sclerosant in the veins. We use ultrasound guidance for some of them and some of it is visual.

We also do what's called TIRS, or Terminal Interruption of the Reflux Source. This is for the most severe patients with venous ulcer disease. We will commonly see the large refluxing veins deep underneath the skin surrounding a venous stasis ulcer. Those can be injected and ablated and it significantly improves the venous flow. It significantly improves the venous flow and ulcer bed and doesn't make the ulcer heal, but it allows it to go through a healing process over usually several weeks to months and usually keeps it from coming back. So it's actually an integral part of treating this ulcer disease effectively.

So sclerotherapy. What do we use? These are the sclerosants that have been tried. I can simplify this and tell you that the very early treatment, which was hypertonic saline. The advantage is that it's cheap. It's easily available. It typically does not create damage if it extravasates outside the vein. The problem is it's extremely painful to the patients. And when you have a lot of injections to do, it's poorly tolerated. What almost everybody now uses is either sotradecol or polidocanol.

The advantage of sotradecol is that it's cheap, it is painless, but it can be damaging to the tissue around the vein if it gets extravasated. And it very commonly gets extravasated. What we use and what most people use now is polidocanol. Polidocanol comes in a preparation that we can foam in the office or it comes as Verithena, which it comes in a can that's already foamed. The advantage to it is that it's painless, it's very effective, and it doesn't create damage to the surrounding tissue if it extravasates outside the vein. The problem is it's more expensive, but it works very well.

The potential complications, fortunately, are also very unusual. We worry about DVT, but we rarely ever see it. We also worry about post sclerotherapy hyperpigmentation, especially in young women. That we also rarely see, but occasionally, and it's probably from the inflammation caused by clotting of the vein. We do see superficial thrombophlebitis. Almost always goes away. One of the chronic problems that we can see afterwards is what we call matting. This occurs frequently when a sclerosant has been given before the ablation of the saphenous vein has been done. So it looks like a rash, but it's tiny, tiny little [INAUDIBLE] that are very difficult to get rid of once it's there. So before doing sclerosant therapy, we'll virtually always ablate the saphenous vein.

Let me talk just a minute about phlebectomy. Phlebectomy is where we take the veins out. We do it in the office. It's very effective for removing large varicose veins. It can be life changing for a lot of patients who have lived with these huge veins for a long time. This is one of our early famous patients. Was a coach. Wouldn't ever wear anything but long pants. And literally was life changing for him, because he started wearing shorts after this procedure. And we continue to follow him.

Let me go just a little bit. I want to talk just a little bit about DVT and thrombophlebitis. Virchow's Triad you may recognize as hypercoagulability. Stasis in the vascular injury, which sets up clotting in the venous system. Iliogemoral DVT versus femoropopliteal versus calf DVT are completely different. The more proximal, the more severe, and the more likely the patients are to get long term post thrombotic syndrome. So we treat those much more aggressively.

Our goals of treatment, obviously, are to prevent propagation and pulmonary emboli, but most importantly to prevent post thrombotic syndrome, which can be devastating to the patients. This is what post thrombotic syndrome looks like. Not only skin changes and swelling, but a lot of pain involved, and lipodermatosclerosis, which is the discoloration of the skin and scarring underneath. And then ultimately, venous stasis ulcers.

This is from 10 years ago, a view of the literature. And the surgical society decided that looking at all of this data that acute iliofemoral DVT should be offered a strategy of thrombus removal. So really for the last 10 years, everybody's been looking for the best way to remove clot in the acute setting. And this is what we've had over the last 10 years.

The Cragg-Mcnamara catheter is catheter directed thrombolysis, which for older clot doesn't work as well. We had a Trellis device which was removed from the market about a year ago. Angiojet's been around for a long time but also not very good for chronic DVT. We do use the EKOS ultrasound facilitated catheter directed thrombolysis. But again, for old clot it's not very good.

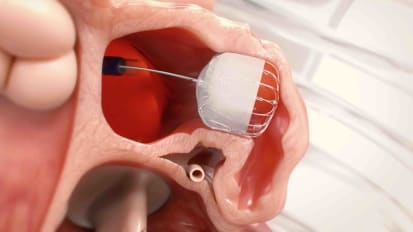

The best thing that we have is a new device called a ClotTriever. This is what it looks like, and it's designed for treating DVT. It's a large nitinol cage with a coring element and a retrieving sheath that usually goes into the popliteal. And it's fairly effective at removing a large amount of clot with a reasonable amount of time, and it has good results.

This is the CLOUT registry, which looked at the-- it was just presented in 2019 at VIVA. 50 patients followed out for 30 days. And this was a combination about a third acute, a third subacute, up to six weeks, and then chronic DVT patients. 75% effectiveness in removing almost all of the clot. Low major adverse event rate. And at 30 days, these values remained patent almost 90% of the time with very low complication rate.

This is what this device looks like. This is the nitinol cage and the inferior vena cava. And this is the coring element. And it's brought down. It literally shears the clot off of the vein wall and it comes down to the popliteal where this retrieving element and sheath then pull the clot out of the body and into this hub. It's a very large sheath. So it's not a totally benign procedure to do, but you get a lot of clot out. This is a thermal vein that's occluded. This after removing a large amount of clot. This is what the ultrasound looks like and clot removing. And this is iliac vein and ephemeral vein after some cases.

So what we do now is treat aggressively the iliofemoral disease with interventional therapy below the calf. Below the knee in the calf deep veins, we treat with anti-coagulation. The femoropopliteal is really a case by case. So young active patients that are very symptomatic, we will try to remove the clots.

Just a moment about May-Thurner syndrome. This is a proximal occlusion usually of the common iliac vein on the left by the right common iliac artery. It goes now by non-thrombotic iliac vein compression, because we see it classically on the left, but now we see it on literally anywhere in the right or the left leg. This is a classic patient. You can see the aorta coming down and the calcification in the right iliac artery compressing the left common iliac veins. Sort of classic X-ray.

This is what the intravascular ultrasound looks like. Right here you can see this is the iliac vein compressed. This is what it should look like beyond the compressed area. And this is where it's compressed. This is a 3D image and really shows how not only the common iliac on the left but the right leg as well, more distally on either side because of tortuosity, because of aneurysms and various anatomy can compress either the right or the left. So we now look with CT venograms and MRVs to look for proximal compression in our more severe patients.

This is one of our early patients with classic May-Thurner syndrome. Left leg enlarged, high grade compression and the left common iliac vein. After stent and six months, her leg was back to normal.

Let me present one case, and we'll be done. This is fairly recent, about a month ago. A 44-year-old patient came with a left leg DVT. Turned out on CT venogram also to have left illiac vein occlusion from external compression. And this is what the femoral vein looked like on the left. Clot filling the proximal part of the femoral vein. This is the iliac vein, which completely occluded.

This is the clot ClotTriever coming up from the left popliteal. And this is pulling the clot down into the sheath and removing it. This is a picture after removing the clot and before the iliac vein stent. Down to the bottom right is after the iliac vein stent has been opened. This was May-Thurner, which then created DVT. And this is the femoral vein on the next to last. And this is the clot that was retrieved. You can see on the far left the nitinol cage. That was full of clot that was removed.

Let me thank you, number one, and show you a short video that'll show you pictures of our new Vein Center that we're so proud of.

[VIDEO PLAYBACK]

- --Vein Center at Austin Heart. We saw our first patient in July of 2010. And I'm excited to share with you our new, state-of-the-art clinic, treating patients with venous disease.

- [INAUDIBLE] across from the Heart Hospital. Patients can proceed through [INAUDIBLE] right outside our front door. Upon entering, you'll be [INAUDIBLE] and will soon be escorted to one of our bright exam rooms, where you will meet with one of our experienced interventional cardiologists. [INAUDIBLE] is a very common problem that affects half the [INAUDIBLE] population. If you have symptoms such as pain and cramping in legs, bulging varicose veins, leg heaviness, or leg fatigue, ask your doctor [INAUDIBLE]. If treatment is necessary, you will be scheduled for [INAUDIBLE] one of our state-of-the-art [INAUDIBLE], where you will receive excellent [INAUDIBLE] care.

- At the Vein Center of Austin Heart, our [INAUDIBLE]. For more information, visit our website or call 512-459-VEIN. Thank you.

[END PLAYBACK]

MATT SELMON: So I think we had a question. What percentage of patients require follow up treatment? Our routine is to see the patients one week later. We reimage to make sure they don't have DVT. And at that point, we'll do sclerotherapy if there's large tributaries are distil, a large distil great saphenous or any sort of tiers around the deep system so that we complete the ablation procedure.

And I would say that's probably somewhere around 20% of the patients that require additional treatment afterwards. Most of the patients in the five to 10 year range, if they had significant venous insufficiency to begin with will get either a large accessory saphenous or large tributary that can usually be injected. So we'll see a lot of patients that are out 10 or 20 years that need follow up treatment, and that's pretty common. I'd say more than half the patients.

As part of the virtual medical education webinar series, Matt Selmon, MD, FACC, discusses the epidemiology and prevalence of venous disease, along with various treatment options.

Related Presenters

Dr. Matthew Selmon is a native Texan who spent 22 years in the San Francisco Bay area as a practicing cardiologist, clinical researcher, and cofounder of Lumend, maker of the Frontrunner and Outback total occlusion devices now sold by ...

Related Videos