Chapters

Transcript

SURAJ: All right, Maggie, I think we can go ahead and get started here. So welcome, everybody, back to our COVID series of Grand Rounds, where Dr. Redfield is going to be introducing her friend and our speaker for today, Dr. Senni. But I'll turn it over to Dr. Redfield. Dr. Senni, you can go ahead and start sharing your slides if you'd like.

MICHELE SENNI: Yeah.

MAGGIE REDFIELD: All right, let's see if they come up. Sorry, I'm at work, and my camera is not working. So if you could go back to slide number one.

MICHELE SENNI: Sorry?

MAGGIE REDFIELD: Go back to slide-- yeah, there we go. So it's my honor to introduce Michele Senni, who is going to share his experience, the Bergamo experience with COVID-19, with a focus on cardiovascular disease.

Michele is the chief of the Cardiovascular Department at the Papa Giovanni Hospital in Bergamo, Italy, which many of you know really was the epicenter for COVID in Italy and in Europe.

He is associate editor for the European Journal of Heart Failure, and really a leading heart failure specialist in Italy and in Europe, and heavily involved in the European Society of Cardiology, and wrote a nice monograph about the Bergamo experience with COVID earlier this year. He has over 230 publications and is in several ESC heart failure working groups. He is involved in multinational clinical trials and registries.

But dear to us was his time here as a CV Research fellow in 1996 and '97. Do you want to go to the next slide? And Michele performed a study that was really my first, I think, really important paper, and made the novel observation defining the incidence of HFpEF and HFrEF in Olmsted County, and showing for the first time, really, that the outcomes weren't that different in the two forms of heart failure.

And this is his second time presenting at CV Grand Rounds because he presented that paper and several other papers that he did while he was here back in 1997. So without further ado, Michele, we're very pleased and very grateful that you agreed to do this for us.

MICHELE SENNI: Thank you, Maggie. It's a really great pleasure to have this right now with you, and it's also an honor. And of course, this give me so many memories about the period that we spent in [INAUDIBLE].

You can see here in the picture, this is my hospital. And this, I'll show you the irony, this is the tower with my department. Actually, there are seven tower around our hospital, in which there is a central tower. And every tower is a different department. This truly is my hospital, it seems.

And this is the upper town, the oldest part of the city. All of you are invited to come to Bergamo. This is the picture that the people of Bergamo want to give to as for thanking us for the work that we have done in the COVID period.

So I think the first question that probably everyone wants to know is why Northern Italy, Bergamo, particularly, was so infected by COVID-19. Well, we have to remember that the Italian people are truly elderly since the mean age for the male, that is 81 years old, and the mean age of for the women is 85 years.

And then we are the typical Italian way to publicly display our affection, using hugs, for instance. And this is something that is difficult to leave and don't use every day.

It has just been calculate that the daily contacts of a person is truly different across, for instance, Europe. As you see, Italy, every Italian people has a mean contact with 17 persons; in France, for instance, 10; in Germany, 7.

Another reason that we are to keep in mind that can explain-- the pollution. Unfortunately, this area is one of more polluted in the world.

Then there is another factor at play for another important role was the fact that it was denied the lockdown in an area close to Bergamo in which there was a small hospital. And they started to see COVID infection, but they didn't recognize the beginning then until it was truly epidemic [INAUDIBLE]. But the region didn't want to close because that was a truly industrialized area.

Finally, and probably one of the reasons why this was spread all over Northern Italy, was the championship soccer game between Atalanta and Siviglia, in which 44,000 people from Bergamo went to Milan to look at this soccer game. And this probably amplified the effect. In fact, also Seville, afterward, was infected by this infection.

So our hospital had to rapidly increase beds for COVID patients. As you see, we have around 800 beds in our hospital. But in the peak of the period, we had 498 patient beds dedicated to COVID. An the remaining 253 others were for the other diseases. But what is the main thing, that of more than 100 intensive care beds, 88 were dedicated especially for COVID-19 patients.

And immediately, we started with an [INAUDIBLE] reaction that established the crisis unit made by a multidisciplinary dedicated team. And for increasing the available personnel, we dramatically reduced the elective surgical procedure, and we reduced the outpatient activity only to the emergency or urgent visits.

And then, we set up a specific training program for nurses and the physicians, because we enroll all the physicians available. Microbiologists, pathologists were involved in treating these [AUDIO OUT] patients in these special COVID-19 units. And unfortunately, we have a high rate of infection of HCP. And for example, 30% of cardiologists have been infected, including myself, unfortunately.

And I think it raised clear an intersection between COVID-19 infection and the heart. And there are still open questions that, for instance, the impact of cardiovascular morbidities on outcomes; the increase of thromboembolic events, the prevalence of myocarditis; the significance of an increase in troponin; the different prognosis in acute current syndrome; or the role of the heart in the high mortality rate of these patients. I will try to answer some of these questions, looking at our experience that it give you some data of a new study that we have conducted.

Regarding the myocarditis, to say, the MINOCA, or Takotsubo, among almost 2,000 COVID-19 admissions for our hospital, the echocardiography was performed in approximately 20%. I didn't import this. Sorry. But in cardiology, were admitted around 200 patients. An echocardiography, roughly, was performed in 92%, 95% of cases using also [INAUDIBLE], we call a fast echocardiogram.

As you see, regarding the prevalence of myocarditis, MINOCA, or Takotsubo, we have this similar prevalence in Bergamo, in Milan, and in Brescia, in which the cases were very, very few. And so regarding the significance of an increase in Troponin, we know that hypertension and cardiac disease are frequent comorbidities of COVID-19, and they are associated with more severe symptoms and poorer outcome.

However, there are limitations in previous studies that are mainly related to the-- based on from one or two centers, included few patients. And most studies were, to remind you, come from China.

So we conducted together with Micrometra, that we check there together from Brescia. This multicenter, retrospective, observational study enrolling consecutive patients with COVID in 13 Italian cardiology units from March 1st to April 9th. And we enroll-- we excluded patients with acute coronary syndrome. And the elevation troponin level was defined as a value above the 99% percentile of normal value of each laboratory.

So you can see that around 614 patients, 148 patients died. And the mean age was-- the patients that died were elderly, more male. And they had more history of hypertension, more history of dyslipidemia, heart failure, heart afibrillation, coronary artery disease, COPD, and CKD. And they presented with lower mean ejection fracture.

In terms of laboratory values, you see that these patients were reminded anemic, a little bit more, with less value of the GFR, with higher CRP and procalcitonin. And the level of troponin was much higher in the patient that died, compared to the patient that remained alive. And a similar result was for NT-proBNP.

And when we compared normal troponin versus elevated troponin, you see clear there was an increase in [INAUDIBLE] mortality in patients that show an increased level of troponin.

And when we tried to look at the independent variable, you see that the multivariable analysis, the age, the oxygen separation, the CRP, and finally, troponin, with a test outside range of 1.71 were the most significant variable for independent, for mortality.

And comparing the normal troponin versus elevated troponin in which 45% of patients had elevated troponin, you see that adding elevated troponin has an impacting term of sepsis, renal failure, multiorgan failure, and heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, and death, of course.

In conclusion, high prevalence, around 45%, of patients had a elevated troponin. Elevated troponin is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality, and is also associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular complications during the hospitalization.

Moving to the next question, open question. There is a different prognosis in acute coronary syndrome in COVID patients compared to patients without COVID. We know that COVID seemed to target cardiovascular system organs besides lungs. The reports have suggested that patients with AMI may have an impaired outcome.

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed-- plaque instability, type I MI, or mismatch between oxygen demand and supply, and they would be type 2 MI. We, therefore, look at 48 consecutive patients admitted for acute myocardial infarction, 36 with STEMI, and 12 with NSTEMI, diagnosed with ECG, high-sensitive troponin I, and symptoms, admitted to our center between March 8th and April 9th.

We have 22 COVID-19 patients, and the coronary angiography and interventional procedures was performed according to the standards. The program endpoint was the in-hospital all-cause mortality.

Looking at the demographic data, we see that the mean age was similar between the two groups, although the patient with an age greater than 75 years was more frequently the COVID-19 patient. Male gender was similar in the two groups. A BMI was similar, and also in term of obesity.

The baseline characteristic showed the COVID-positive patient and the more history of hypertension, more history of diabetes, more previous PCI. And regarding the clinical presentation, basically, I was involved frequent in the COVID patient, as well as fever, whether chest pain was present in the same rate in the two groups.

STEMI was more frequent in the COVID-positive patient, instead of NSTEMI was more frequent being COVID-negative patients. And what's interesting, when we look at the time of presentation to the hospital, you see that approximately 30% of patients in both groups presented late around the sixth hour, a disease related to the breakthrough that we had in Bergamo during the first period in which the patient didn't find the ambulance or didn't have the fear to come to us. And this was probably the reason of why this great delay.

At presentation, the patient with COVID positive were with more systolic blood pressure less than 100 millimeters of mercury. They had more [INAUDIBLE] Class 3-4. And they had more left ventricular ejection fraction, less than 35%.

And the gas exchange show that these patients had a lower oxygen saturation. And the interesting and probably more important, they have a [INAUDIBLE] ratio greater in these-- lower, sorry-- in the COVID compared to the non-COVID. And when we look at the group with this ratio below 100, you see clearly that one fourth of these patients had this [INAUDIBLE].

More patients with COVID were ventilated with cPAP. And when we look at the cPAP end then-- to end the [INAUDIBLE] intubation, this was not frequent in the COVID patient.

In terms of procedural details, we see that there are few differences between these two groups. There was a tendency to have more multivessel lesions in the COVID patients. And there are more recurrent thrombus in the COVID patient compared to non-COVID patient.

In terms of in-hospital outcome, that was the primary point of this observational study. You see clear that there was an amazing difference in terms of results regarding the all-cause death. 45% of patients with COVID died compared to 0% in non-COVID group. The cause of death were acute hypoxic respiratory failure or a combination between cardiorespiratory failure. Just two cases, one due to cardiogenic stroke, and the other one could be disseminated intravascular coagulation.

There was a tendency to have more stroke in the COVID patients. And interesting, you see, we didn't have a difference in terms of second of pulmonary embolism in the hospital outcome. For sure, these patients were treated with anticoagulation during their hospital stay.

In conclusion, in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 patients presenting with AMI remains very eye in spite of PCI. The coexistence of respiratory failure seems to be an issue of importance in selecting patients who might benefit from invasive procedures.

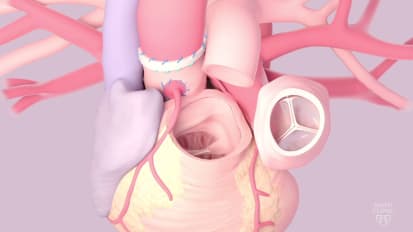

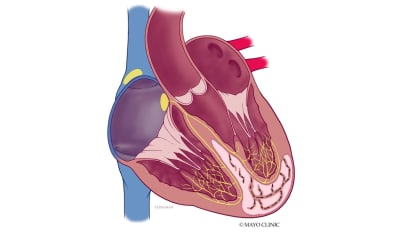

The last question is the role of the heart in the high mortality rate of these patients. We know that interstitial pneumonia, that it is a typical characteristic infection of coronavirus. It is often characterized by ARDS. And ARDS is typically characterized by inflammatory alveolar edema associated with stiff lungs, intrapulmonary shunting, and a frequent pulmonary hypertension. This is the typical characterization of ARDS.

We, therefore, selected 21 patients that underwent right-heart catheterization, and they were admitted to intensive care unit. And we compared this group with a one to one control group, matched for age, sex, and body mass index.

The COVID group was a group of unselected patients admitted to cardiac surgery ICU beds. And in these ICU beds, the intensivists routinely performed right-heart catheterization. Of course, we excluded patients with reduced ejection fraction, significant COPD, pulmonary vascular disease, cirrhosis or malignancy, and acute extensive pulmonary thromboembolic disease. The control group of outpatients that underwent right-heart catheterization for an unexplained non-cardiac dyspnea.

These are the timeline data we have for patients that underwent right-heart catheterization. So the symptoms before stabilization, the median was six days. The admission to intensive care units was four days at the time between ICU intubation to right-heart catheterization is four days. So median, you can have 14 days between the starting of the symptoms to having a right-heart catheterization.

The COVID-19 patients, in terms of age, male. BMI were similar, of course, because measured it to control group, the mean age was 68 or so. 86% were male. And globally, more than 80% of patients were overweight or obese. 38% of these were obese.

Looking at the baseline characteristics, you see that patients with COVID were at more diabetes, less dyslipidemia, less COPD, less heart afribillation. In these patients, the troponin was normal. The hemoglobin was slightly lower. The renal function was normal.

There was an inflammatory status to show by c-reactive protein, a mild increase of procalcitonin. The D-dimer was slightly higher, 1,400. And fibrinogen was 564.

The echocardiography data show that the dimensions of the left atria, of the left ventricle, and the ejection fraction in the COVID group were normal, although were higher in time of ejection fraction, a lower internal [INAUDIBLE] ventricular dimension, left heart dimension volume index, and compared to the COVID.

Why don't we look at the dimensions, the mass, of these patients? You see that was a thickness of the septum and the [INAUDIBLE] were higher in the COVID group compared to the negative COVID patients. [INAUDIBLE] were similar. However, in term of left ventricular geometry, there was a significant difference between the two groups, [INAUDIBLE] concerning, regarding the consenting and [INAUDIBLE] was much, much higher in the patients with COVID.

And the right ventricle dimension and function between the two groups were similar. And globally, the right ventricle dimension was normal and the function as well in the patient with COVID positive.

The right-heart catheterization showed that the COVID group had higher mean pulmonary arterial pressure compared to the COVID negative, higher wedge pressure, higher right arterial pressure. The pulmonary vascular resistance were normal and similar to patients without COVID.

The cardiac [INAUDIBLE] and the cardiac index were higher in the COVID patients, with a higher [INAUDIBLE], that means [INAUDIBLE]. That is a shunt in the lower systemic vascular resistance compared to the COVID-negative patients, or non-COVID.

Looking at the relationship between intrapulmonary shunt and lung compliance, you see that there was a clear inverse relationship. And these inverse relations was present even based when we look at the lung compliance and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure.

So looking at these data, we can hypothesize that there is probably a vicious circle between the lung and the heart. In fact, starting from the coronavirus that is a cause of interstitial pneumonia, this interstitial pneumonia leads to a reduced lung compliance. The lung compliance per se is a cause of an intrapulmonary shunt.

However, in the presence of coronavirus, we have like a blanket hypoxis form a vasoconstriction that through probably mitochondria injury or ACE/ACE2 advance that we don't know exactly, that delay further promoting the intrapulmonary shunt.

This intrapulmonary shunt, along with the inflammatory status, leads to an increased cardiac count that increase the left ventricular feeling pressure, which can play a role. The fact that we see a left ventricular consenting and remodeling may be due to the involvement of cardiac ACE2 receptor. And at the same time, the hypoxemia leading to hyperventilation leads to an increased [INAUDIBLE] pressure.

At the end, we have an increased wedge pressure that leads to non-congestion that leads to a further reduction of the lung compliance, so creating a vicious circle between lung and heart.

So in conclusion, we can say that COVID-19 seemed to promote this vicious circle between the lung and the heart characterized bu a low pulmonary vascular resistance that is coherent with a blunted hypoxic vasoconstriction facilitating a high intrapulmonary shunt fraction, a high cardiac output, and the high frequency of isolated post-capillary pulmonary hypertension that could contribute to lung stiffening and to severity of respiratory failure. Thank you so much for your attention.

SURAJ: Thank you. Thank you. Dr. Senni. And Dr. Friedman, our chair, wanted to make a couple of comments. So I'm going to hand over to him briefly.

DR. FRIEDMAN: So Dr. Senni, first, thank you so much for joining us. We've been watching carefully as our friends in Europe and around the world have been fighting this initially, and before it's now in the US, of course. And we're learning a lot from your experience.

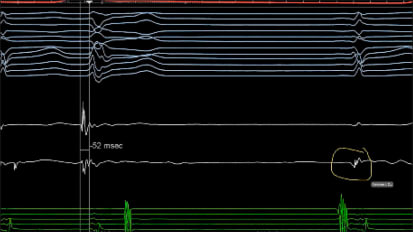

I had a couple of questions. There's two of them, actually. The first one is, a number of us have been very interested in the ECG changes associated with COVID and whether you've noted any specific patterns or things that have really sort of jumped out at you. You commented on some of the echochardiographic features.

And the second thing is, in your vicious cycle, at least I interpret it to mean that commonly the lungs begin, and then the heart, and then back to the lungs. How often do you see it begin with a cardiac involvement? And we've seen these cases of pseudo-myocardial infarction that may reflect COVID myocarditis. How prevalent do you think that is? We'd love to get your thoughts on that.

MICHELE SENNI: Unfortunately, I missed-- I lose your first question because there was some problem with the--

DR. FRIEDMAN: Oh, sure. The first question was whether you observed any specific or characteristic ECG patterns in association with the infection.

MICHELE SENNI: OK. Honestly, we didn't find any specific EKG changes in this COVID infection. Although we perform it [INAUDIBLE] 19,900 patients. But of course, in an hour, around 200 patients that were admitted to cardiologists with COVID, we didn't find any specific EKG changes. This is the experience also from other centers in Northern Italy.

Regarding the second question of myocarditis-- and I don't have any experience. We had just one case of uncertain myocarditis. And I ask this to the other center, to Milan and to Bergamo and to Brescia if they have other experience regarding this, because we are discussing if we're to do something on this topic.

And but we didn't have-- we didn't find anything specific. If you will allow me, I'll show you what our pediatrician together with our pediatric cardiologist just published five days ago in Lancet regarding the Kawasaki-like disease.

And this is something that is interesting. And they said they compare these two group. One is 10 patients that they noticed during the last period, February 18 to April 20, compared the previous five years.

And you see there was an incredible higher incidence-- 30-fold-- of Kawasaki disease. However, there are differences between these two groups because the large group was older, the mean age was higher. The cardiac involvement was present in most of the cases, 6 of 10. The second group were just 2 of 19, the first group.

The macrophages division syndrome was zero in the first group, a 5 of 10, so 50% of cases, where we found this macrophage activation syndrome. And more important, the need for adjunctive steroid treatment was in 8 of 10 cases in the last group, so in their recent group.

Although there are a lot of discussions about these points, if it's a cytokine failure or storm, the cause of this syndrome. We didn't see, honestly, in adult patients. There are pediatric patients, different. But it can teach us something more about how can be the involvement of the heart, due to the virus that was really fueled.

They didn't perform mitochondrial biopsy. But when we look at the data recently published in New England, also, the data are coming from [INAUDIBLE], the number of the virus inside the mitochondria is really low. And so, therefore, thinking that this is the cause of myocarditis is different.

Maybe, but at the same time, the disease that a cytokine storm is correct for defining a myocarditis? I'm not sure. I don't know, but it's something that is interesting. And probably, we can learn more from the pediatric patient.

SURAJ: And Dr. Senni, there's two questions from Dr. Rihal regarding hemodynamics. And he was asking, could you comment in more detail on the pulmonary mechanics specifically ventilator pressures and how they may interact with the cardiac outputs? And also, does prone ventilation have any role or any effect as well?

MICHELE SENNI: Yeah, this is a good question. And we cannot exclude completely that some of these results were related to the influence of the ventilation on the hemodynamics value. However, we can say that the mean [INAUDIBLE] report was truly low, was 10 millimeters of mercury.

And therefore, although maybe there are some influences, probably they are not so important that in terms of effect the hemodynamics. Interesting, what is true, that the wedge pressure was still high and low. And therefore, with people, we could've expected more high, for instance, right-heart pressure that there is. But the pulmonary wedge pressure probably is not affected by the high level of people that how ever was limited in median value.

SURAJ: And have you had much experience with prone ventilation and seeing any effect on hemodynamics with that?

MICHELE SENNI: That's a good question. Unfortunately, we didn't perform in prone or supine position. We know that there is a positive effect. But all of these patients were in supine position.

SURAJ: OK. And Dr. Redfield was saying that the pulmonary vascular response you're seeing seems unique to COVID-19. And she was wondering, does the intensive care colleagues have any experience with other infectious or inflammatory pneumonias? And do they mimic this?

MICHELE SENNI: And this is a good question, but in general, if we look at the data published on ARDS, we should expect that an increase or at least normal pulmonary vascular resistance, more increased because these increases are mainly related to the hypoxic vasoconstriction, because is the way how to reduce the shunt.

At the same time, most of the time, these patients have thromboembolism or thrombosis. So in influenza, I don't know. But in the ARDS, the scenario is a little bit different compared to this longer situation that we found [INAUDIBLE] in COVID patients.

SURAJ: Understood. And Dr. O was wondering, with intrapulmonary shunt and increased wedge pressure, it would have been informative to also perform contrast shunt imaging, and also diastolic function assessments. And he was wondering if you have any contrast and diastolic function assessments in your cohort.

MICHELE SENNI: Yeah. We performed and we should've report in the manuscript. Thank you for that. In all patients which we performed the echocardiography, in which we didn't perform it in all 21 patients. Only we perform in 14 patients.

And in all patients we perform the bubble test, we didn't find the shunt between the left and the right side. So we didn't find any shunt. And in terms of diastolic function, it was quite difficult to assess in most of the patients. In those in which we assessed the diastolic function, we found a slight increase of EE prime, but it was a relatively limited number of patients.

SURAJ: Understood. And Dr. Lehrman was wondering, have you observed any vasculitis?

MICHELE SENNI: And this is another important question, thanks. Actually, we performed more than 50 autopsies. And we sent 36 hearts to [INAUDIBLE]. And we are waiting for the result to see what's going on in the vessel, as well in the muscle. And we will see the results, but it is a good question.

What I can see from that the microscopic assessment of these autopsies, there is a clear hypertrophy of the ventricles. There is congestion in the lung and the liver. So this is confirmatory with the increased wedge pressure, and also microthrombosis in the lung vessel, but also in the heart [INAUDIBLE]. But we don't have, so far, clear results.

SURAJ: Understood. And Dr. Redfield just had another question. Basically, as you start to see follow-up patients after their hospitalization for COVID-19, have you seen any evidence of persistent pulmonary dysfunction or new heart failure?

MICHELE SENNI: Unfortunately, we just started with the follow-up, and we don't have, so far, data about that. But this is something that we want to check.

SURAJ: Understood. Dr. Redfield, I know there's only a couple minutes left before 8:15. Do you want to make any final comments?

MAGGIE REDFIELD: Sure. This was really great, Michele, very interesting, all three of the studies that you've done.

I think we're just all fascinated with the cardiac manifestations, and we've seen some bizarre stuff here, and elsewhere in the United States. Although, separating out what might be myocarditis from the typical cytokine storm and cardiac biomicrostorm that you see with any sort of ARDS is difficult. So it sounds like at least you're not seeing evidence, even in this very high-risk population that you've looked certainly more carefully than any other literature with echo and hemodynamics, a high incidence of myocarditis. So that's very helpful.

And I'm fascinated by the endothelial cell ACE2, and how this could be causing endothelial dysfunction, as I know you're thinking of, and that that could lead to a heff-peff-like picture over long-term follow-up. So that will be interesting to see if that develops. But thank you so much. This was really excellent.

MICHELE SENNI: Thank you. Thank you, Maggie.

SURAJ: [INAUDIBLE] and thank you.

MICHELE SENNI: Thank you.

SURAJ: Thanks, everybody, for joining. Have a good day.

MICHELE SENNI: You too. Thank you.

DR. FRIEDMAN: Phenomenal lecture, appreciate it.

MICHELE SENNI: Thank you.

In this Cardiovascular Grand Rounds video, Mayo Clinic cardiologist Margaret M. Redfield, M.D., hosts guest faculty Michele Senni, M.D., chief of the Cardiovascular Department at Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, Italy. Dr. Senni recounts Northern Italy's experiences with COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease.

Related Presenters

Interests Amyloid cardiomyopathy Diastolic heart failure Heart failure remote monitoring Natriuretic peptides Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure Systolic heart failure Tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy

Related Videos